- Hater's Guide to Living Well

- Posts

- "So what do you do?"

"So what do you do?"

I came to this party to trade resumes, of course.

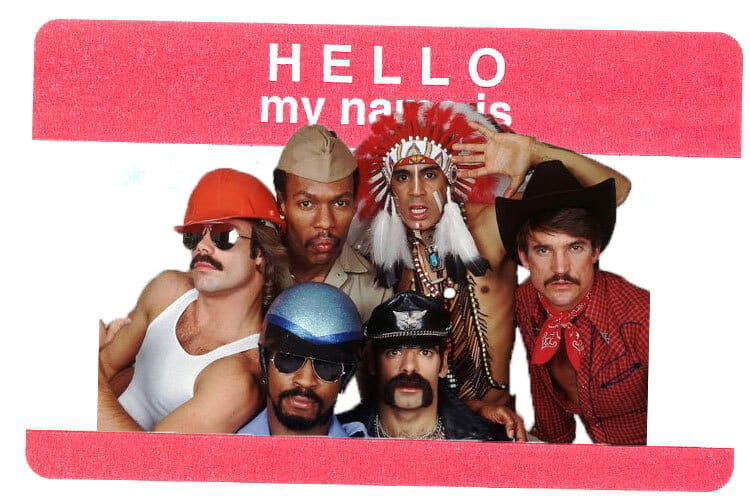

Tag yourself.

As a professional question-asker, I can say that asking good questions is hard. And I can tell you that it’s almost impossible to ask really good questions after a long day of professional question-asking. Which is why I’ve sometimes fallen back on The Worst Question when I meet a new person.

“So what do you do?”

It’s almost embarrassing to hear yourself ask this question, knowing full well what a snoozefest it is to answer — and how remarkably little you learn about someone. Maybe the last really great, straightforward way to get to know someone came from those early aughts chain email questionnaires. Back when you would sit patiently for the six minutes it took your computer to dial up the world wide web so you could log into your yahoo dot com email and answer 100 questions about yourself to then forward to your best friends.

(I tried to find one of these questionnaires and the best I could locate was this 2008 Seventeen blog post.)

Asking people what they do for a living is such an uninspired way to learn a little something about them. While I’ve certainly met a few people whose jobs really do seem to be their personalities (teachers on occasion, some historians, and a remarkable number of marketers), finding out that someone works for an office supply company doesn’t offer a boatload of insight. It can even stop a conversation before it ever leaves the station: Oh, you work for Office Depot? That’s crazy. What’s a stapler going for these days?

I recently interviewed J. Eric Oliver, a University of Chicago professor, about his upcoming book, How to Know Your Self, and thought he could offer a little insight on the topic. Oliver — a political science professor — has been teaching a course called “The Intelligible Self” at the university for two decades, in which he explores the self from the molecular level all the way up to what he refers to as the egoistic self, or our way of understanding ourselves in society.

To begin with, Oliver points out that asking someone what they do for a living is a pretty uniquely American question. In essence, we’re demanding someone tell us what they’re accomplishing. He references a chapter in his book that offers a better example of trying to connect with others, called the cycle of intimacy.

“How we really connect with people is kind of based on three things,” he says. “What are the things that we have in common? We tend to like people that we have more in common with. The second thing is vulnerabilities. So once we establish some commonalities, can we share some vulnerabilities? These would be things that would be quirks about us that you wouldn't necessarily see at the surface. And then the third part of the cycle is then offering affirmations. So when someone shares vulnerabilities or shares a commonality, you offer an affirmation.”

Oliver says when he’s on a plane and someone asks what he does, he’ll say he teaches American politics — which inevitably results in his seatmate telling him how interesting that is, considering our current state, and then sharing their own political theory, which gets the conversation moving. (“If I'm not feeling talkative, I say I teach statistics.”)

Asking someone what they do for a living may not be the absolute worst question, but you may find yourself doing some serious legwork to find some sort of common ground — especially if you don’t find the profession particularly energizing (sorry to the statisticians!). And, again, by asking someone what they do for a living, it starts to feel like they have something to prove to you, a perfect stranger.

“(It’s like) we're in some sort of contest where we're feeling each other out, some sort of status hierarchy,” Oliver says. “Instead, it's trying to find, I think first, just find commonalities, and then sharing vulnerabilities or offering affirmations.”

I have a list on my phone of what I think are solid getting-to-know-you questions — and I think they’d stand up to a test of Oliver’s cycle of intimacy:

What was your favorite childhood vacation and your favorite vacation as an adult?

What is your favorite breakfast food (when cooking for yourself vs. at a restaurant)?

What are your three favorite grocery stores?

(For people in your town) What are neighborhoods you don’t really find yourself in anymore, even though you used to spend a good bit of time there?

These are by no means hard-hitting questions but I would bet you just answered them all in your own head!! Imagine finding out you used to spend all of your time in Bridgeport during the same years your new friend used to. Or that they have a great Asian grocery store recommendation you’ve never heard of. Or maybe you bond over how crispy waffles rule so hard??

Granted, you do run the risk of scaring someone off by immediately demanding they explain why they had a meaningful experience in the Poconos as a child. But think of the opportunity you’ve offered your friend’s co-worker/cousin/neighbor that you just met: You gave them a fun little prompt that doesn’t involve having to explain what being an analytics strategist is (did I make that up or is that a real job?).

Every time I tell someone new that I’m a writer-editor, I brace myself. We don’t naturally know how to follow up even the most straightforward job. You’ll ask me, “What sort of things do you write about,” and I’ll say, “oh, I’ve covered a lot of different topics” and maybe list three. Then we’ll both sip our little plastic cups of wine and smile at the middle distance. What we could be doing, though, is debating the strengths (little snacks) and weaknesses (unreliable produce stock) of Trader Joe’s.

**By the way, I went ahead and answered that Seventeen questionnaire and made a blank copy for you to enjoy as well. Feel free to email it to me so I can learn everything about you and however many cats you have!

Reply